Rob Martin is a former member of the Canadian Forces who hopes to attend Camp Aftermath. Rob was deployed throughout his career and suffered from PTSD following traumatic experiences he had during various postings. In an interview with Camp Aftermath, Rob discussed his PTSD and treatment, and how he hopes to give back and learn more about himself by participating in Camp Aftermath. Donate today to the Camp Aftermath GoFundMe campaign so military veterans like Rob can benefit from the first Camp Aftermath rotation to Costa Rica in 2018.

Camp Aftermath: How did you end up joining the Canadian Forces?

Rob Martin: I was born the youngest of three children, outside of Bancroft, Ontario. Growing up, I was always outdoors. I was always playing sports. We moved around Bancroft a fair bit, up until 1969 when we moved to Coburg, which I call my hometown now. I lived in Coburg from 1969 until 1976 when I joined the army. I went to highschool in Coburg, played lots of varsity sports, but I didn’t do well in class, I was really bored.

At 17, I was finishing grade 12 and I skipped the last couple of weeks – my parents didn’t know. I was actually at the local pool hall one day and my mom came in and grabbed me by my long, curly hair. Then she did a really good thing for me. She asked me what I was going to do, and when I said I would just figure it out, maybe live at home, she said: ‘Nope. That isn’t going to happen.’ And she literally kicked me into the army at 17. She signed me into the army at the recruiting centre in Toronto, at Yonge and St. Clair. And so I went off to the army on July 30th, 1976.

Interestingly, my great grandfather was in the First World War. My great uncle was killed in the Third Battle of the Somme,. My father was in the Second World War, in the RCAF and then in the Armored Corps. My brother was in the Air Force. So I guess we did have a military background, but I never really thought of it like that.

CA: Why did you decide to dedicate to yourself to a career in service?

RM: Initially it was a job. I was a Morse code operator, then I became a Russian linguist, and I loved the work. It was the most fulfilling work I’d ever done. I kept going back to Alert, doing that job. So I think it became something more than a job. It became a passion, a vocation, and a profession. I think I morphed into it. I really believed that I was contributing. I kept being recognized for leadership through promotion and I loved the work that I was doing.

Early on I don’t think I was aware of the sense of purpose I got from the military. I think early on it was just like everyone else. I was easily influenced by peer pressure. I was still athletic in the military, but also picking up some bad habits.

I think the transition for me was probably when I was commissioned in 1991. It was challenging. It was always different. I was meeting new people all the time, facing different challenges, but I was part of a team, and being part of a team is critical. Serving together, you take the “I” out of yourself, and you become part of the team.

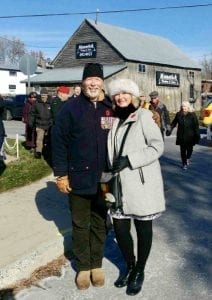

Rob Martin and his partner Dale Randell

CA: What was one of the first signs that you were experiencing symptoms of PTSD?

RM: Well my marriage failed. I was married the first time for 4 years, and spent most of that time away on business. The early 90s were when I started to feel the cost. After my first tour in Afghanistan I felt that something had changed. I understand now that my family was probably walking around on eggshells then, because I had a lot of anger, and it was very vocal. It wasn’t healthy. I was mad for a long time. And my now ex-wife told me to go and get help but I didn’t think there was anything wrong with me.

It really began to come out after my second tour in Afghanistan in 2009. I was the Deputy Commander of the Information Operations Group, and I couldn’t put two sentences together for a business plan. I lost 35 lbs in weight. I was starting to have suicidal thoughts. So I sought help, not on my own, though. A buddy of mine kind of grabbed me by the uniform and asked me what was going on. My body mass was just shrinking from stress, and I even failed my PT test. So I went to my commander and I fell on my sword, and told him that I had to leave because I’m not physically fit to lead. This was on December 9th, 2009.

CA: If you could give yourself advice now about your experience with PTSD, what would it be?

RM: Don’t fight the diagnosis. When you get the diagnosis, you really have to open up your arms to the diagnosis, and not fight it. Because fighting it probably added an extra four years to my recovery, and almost cost me my life. Even when I was getting help – I was on medication, I had therapy – but, I was still fighting it. It’s hard to get through the door the first time, but you have to stop fighting once you get through the door.

CA: What do you think about Camp Aftermath’s novel approach to PTSD treatment through active philanthropy?

RM: So the biggest question we all have when we are going through this journey is what to do when we’ve lost our uniform and we’ve lost our identity. I started asking myself these existential questions about a year into therapy. I had read Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning, and in it he talked about purpose. Forget about happiness, happiness is a tangible thing, but happiness will not generate a good life. Happiness is a by-product of a good life which has meaning. So how do you find meaning in your life? You can heal yourself by helping others heal.

CA: What do you think you will gain from participating in Camp Aftermath’s first rotation in 2018?

RM: There’s a reason why I want to go to Camp Aftermath, and actually the best way to translate this for other people is to use the model of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. From physiological, safety, emotional, meaningful, and self-actualization. What I believe is that the Canadian military met all of my needs. So when you lose a career where all of those needs were being met, then you’re in this dark abyss, I looked at all the programs I’d done and I placed them on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Project Trauma Support is the only one that fit in the self-actualization category in terms of the hierarchy. And Camp Aftermath is going to do that as well, because it’s going to contribute to someone finding meaning that they can then give back to their society, and which is greater than themselves. The philanthropic piece is really beautiful.

I hope to gain greater understanding of myself. In my quest, at times it’s been rather random. I call it my terrible, marvelous journey. It’s been seven years. And I think Camp Aftermath will give me an even greater understanding of who I am as a human.

Camp Aftermath will contribute to that because I want to know what else I can do in the philanthropic arena. I am volunteering with Project Healing Waters, I’m supporting Project Trauma Support, the Veterans Transitions’ Network’s peer support. I do this because it gives me purpose! In helping others who are not as fortunate as you, you can reach a level of stability where you can grow through your injury. And I think that’s something bigger than yourself.